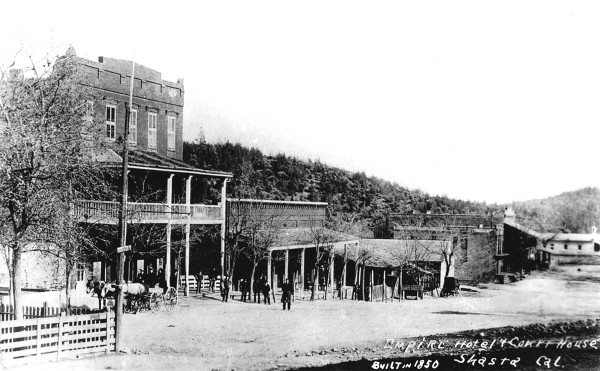

Historic Photo of City of Old Shasta, including the Empire Hotel and the Court House. Photo courtesy Gail Jenner Collection.

As with the rest of California, it was the great Gold Rush of 1849 that opened the doors to Siskiyou County. Harry L. Wells, in HISTORY OF SISKIYOU COUNTY, CALIFORNIA, credits the first mining in this region to Lindsay Applegate who traveled south from Jacksonville, Oregon, in 1849 to mine along Beaver Creek, the Klamath, and the Scott River. In June of 1850, however, prospectors from the Trinity River crossed the Salmon-Trinity Alps and found enough gold to whet their appetites. John W. Scott, from whom the valley and river later derived their names, discovered gold at “Scott’s Bar.” The discovery of gold near Shasta, six miles from present-day Redding, brought miners from the Mother Lode and Sierras up the Siskiyou Trail in search of riches. They came to Shasta (now called “Old Shasta” located near Redding), and continued to use it as base of operations for years. Through the summer of 1849, Argonauts from Oregon and the Mother Lode poured into Shasta. It was a tent city of more than 500 persons by October 1849… But an old mule train built by the Hudson’s Bay Company was all that connected it with Sacramento, 188 miles to the south.

Shasta, aka the “Queen City,” became an important link to the rich mines in the back country (Trinity region into Salmon River country and eventually Scott Valley, etc….) as well as a stage stop. History says a hundred mule trains and teams were known to stop at Shasta on a single night. The railroad signaled the demise of Shasta, which occurred around 1888. Old Shasta was once “THE” city in northern California. Within a year, the “northern mines” were drawing prospectors from every part of the world – perhaps as many as 20,000 – who, “like coveys of scared quail, scuttled hither and thither.” Without roads, the only manner of travel was by foot or by mule train. Few stayed in one place long, though settlements throughout the region boasted booming populations at various times.

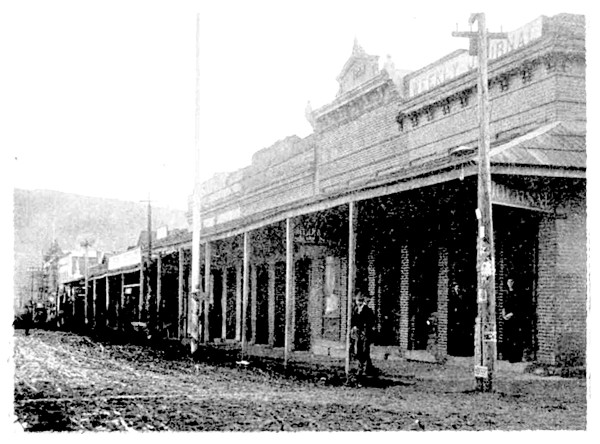

Photo: Early scene of Yreka. Note the building’s sign: “Weekly Journal” – Courtesy Gail Jenner Collection.

The first gold-seekers to Western Siskiyou County followed the waterways, in particular the Klamath River and its tributaries. A land of rugged mountain ranges and steep gorges, the only semblance of an earlier trail led to Oregon, a remnant of the Hudson Bay trapping era. That trail meandered up the Sacramento River, through Shasta Valley, across the Klamath River, and over the Siskiyou Mountains into Oregon. Others traveled up the California coast, or down from Oregon. A very early group of miners to permeate the region was led by John W. Scott (whose name was then given to a valley, a river, and a mountain pass). He and his men discovered gold at Scott Bar in July or August 1850. And later, as reported in the SACRAMENTO UNION, June 23, 1851: “The largest lump of pure gold ever found in California was taken out by Messrs.

Brown, Beach and Forest at Scott Bar on Scott River within the last few weeks and weighed $3,140.00.” It was reportedly free of “spot or blemish.” Scott Bar became a lively mining town with more than 50 residences, as well as stores, boarding houses, saloons, a butcher shop and blacksmith, a hotel, even a drug store. The cemetery dates back to 1857. Prospectors from Trinity River likewise mined the Salmon River region as early as June of 1850. There they established a small post or settlement – the first – called Bestville, in honor of Captain Best, a sea captain, miner and trader in the party who discovered gold with the help of Squirrel Jim, a Shasta Indian who became a ‘friend’ to many whites. When Squirrel Jim died in 1919, he was buried on the Sallie Burcell allotment in Etna.

He died from “the infirmities of old age” and was “about 100 years old”. The richest and most extensive discovery north of the Trinity range of mountains was found near Yreka, but this site was ignored for several months until a party from Oregon camped at “Yreka Flats,” a popular camping ground between the Shasta and Scott Rivers. Most miners passing through were so intent on getting to the streambeds, they never dreamed that gold lay just below the surface of the ground – literally beneath their feet. But one day in March 1851, Abraham Thompson, did do a little ‘scratching’. “After washing three pans of dirt beside a small ravine, later called Black Gulch, a good prospect of coarse gold was found…He took it to his companions and finding ‘little scales of gold clinging to the roots of the long grass,’ convinced them ‘of the richness of their find.’” It didn’t take long for Thompson’s Dry Diggings to mushroom into a tent city, first known as Shasta Butte City, then renamed Yreka. Within six months there were 5,009 men vying for thirty foot claims as well as the water that became more valuable than gold. ♦